My mother - Clemmie Madelyn Croft - grew up in Florida. In fact, her father’s family - the Crofts - moved to Florida from south Georgia before the Civil War. Her mother walked to Florida in 1890 alongside a horse drawn wagon carrying all the family belongings. I think I mentioned in an earlier posting that it took three weeks for them to get from Barwick, Georgia to Dade City, Florida. So, Mom had strong Florida roots - "plenty of sand in her shoes," she often said. She grew up on a farm near

Dade City with an older sister and two younger brothers. She hated the farming lifestyle and left home as soon as it was possible. She attended Florida State University (it was then called Florida State College for Women) in Tallahassee long enough to get a teacher’s certificate and taught school for a couple of years in a rural, one-room schoolhouse in Pasco County. In 1921, she moved to Tampa and found a job clerking in the office of O’Berry & Hall Co., a wholesale grocery distributor. It was there that she met my father.

She and Walter Berg, Sr. were married in 1930. The country was in a deep economic depression.

They kept the marriage secret for a couple of years to avoid one of them losing their job. Company policy prohibited the employment of man and wife. When she became pregnant (with me) they both resigned, moved to Orlando, and bought a little store. They quickly learned that the former owner had alienated the people in the neighborhood. Nobody came in, so Mom started making house-to-house visits trying to befriend the neighbors and get them to come to the store. She succeeded in making many friends, but money was scarce, and the business ultimately failed.

I was born in the apartment above that little store. I never knew how dreadful an experience that was for Mom until 23 years later when my first son was born. He was perfectly formed without a mark on him, and when my Dad saw him the first time, he told me the story of what happened when I was born. Mom was a small woman - barely five feet tall if she stretched a bit. She was 35 years old. They couldn’t

afford a good doctor or to go to a hospital. The only doctor they could get was an alcoholic who had essentially lost his practice. It would have been a difficult birth anyway, but this doctor nearly killed us both. He butchered Mom pretty badly. The forceps the doctor used nearly tore my head off. Dad said that my head was bruised and scratched and contorted all out of shape. They feared brain damage. Mom was unable to have any more children. Mom never talked about the ordeal - never. And, that one time was the only time Dad ever mentioned it. I don’t know whether anyone else in the family ever knew what had happened.

They moved out of the apartment soon after and rented a little house about a block away from the store. The community was called Jamajo, after three developers. Few people in Orlando know anything about Jamajo any more. The area has deteriorated badly, but back then, it was an upper middle class neighborhood with retired architects and other former professionals living there. Revisiting the area a couple of years ago, the only reference I found to the name, Jamajo, was a street by that name. Dad used to tell the story that the "Jo" in Jamajo was Joe Tinker, a Hall of Fame baseball player. He was the legendary shortstop with the Chicago Cubs who started the famous double play combination of Joe Tinker (SS), Johnny Evers (2B), and Frank Chance (1B). They were immortalized by a sportswriter’s poem - "Tinker to Evers to Chance" and all three were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame at the same time - in 1946. Joe Tinker died in Orlando two years later in 1948.

These are the saddest of all possible words,

A trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double--

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

"Tinker to Evers to Chance."

How’s that for a diversion.

Despite the upscale character of the neighborhood, the depression had hit everyone hard. The day I was born was the day that President Roosevelt closed all the banks in the country. Things were grim. Mom said that one day, about a month after they moved into the house, that they were down to their last few pennies, and there was no food in the house. She got down on her knees and prayed for help. Shortly after, Dad found a large turtle that had come up in the yard. He killed the turtle, and that became the next meal - the answer to Mom’s prayer. They held out for a few more months, but finally gave up. That was when Dad swallowed his pride and begged for his old job back in Tampa. I don’t remember any of that. I wasn’t even a year old when we moved back to Tampa.

Mom was the spiritual leader of the family. Every night she’d get us together to read from the Bible and pray. She seldom missed a worship service at the Seminole Heights Baptist Church, and she always took me along. She sang in the choir and held the job of Church Librarian for many years.

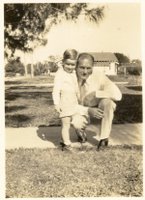

Mom was the disciplinarian of the family. When I misbehaved, she’d cut a switch from a wild cherry tree in the back yard and make me dance. That's the tree behind us in the picture to the right. I think she was a little over protective, at least early on, since I was the only child. I can understand that now, but at the time it made me a little resentful. For a long time, I couldn’t leave the yard, while other kids were roaming free in the neighborhood. When I started to school, I couldn’t stay after school and play as other kids did. If I was five minutes late getting home, Mom would be walking the floor and demanding an explanation. She gradually eased up on that, but I could never run free like I thought other kids did.

My mother was a good cook, and she was also a good seamstress. She made all of her own clothes. For a time, when material was scarce during the war, she made many of her dresses out of used flour sacks. They were pretty nice too. The cloth sacks were printed with a variety of colorful flower patterns. She had a treadle operated Singer sewing machine that she could make fly.

As a cook, Mom tried to learn all the German recipes that Dad remembered his mother making, and she did a good job of it. I guess my favorite cookie was

pfeffernuesse. These were hard, spicy little balls about the size of a large marble - a German tradition around Christmastime. Mom would make about a bushel of them, giving them to all the neighbors, the preacher, the doctor, and most anybody who came around. I’d fill my pockets with them to take to school.

Kartoffelklase und Sauerbraten was one of those German dishes - potato dumplings and a sauce of vinegar soaked beef. That wasn’t served often, but it was good.

It was always fried chicken for Sunday dinner. Saturday was baking day and the day to catch a fryer and wring its neck. Mom was good at that. If company was coming for Sunday dinner, she’d kill two. I can see her now, grabbing two chickens, and with one in each hand, wringing both necks at the same time. When the necks were broken, she’d let the birds flop around on the ground until they died, then plunge them into a bucket of scalding water to loosen the feathers. I’d get the job of pulling the feathers while she’d go back to her baking in the kitchen. Everything got fried except the head and the feet. Dad’s favorite piece was the gizzard. Mom got a breast. And I got the pullybone. When the meat was

eaten, we always made a wish and pulled the pullybone. Whoever wound up with the long end was supposed to have their wish come true. Why don’t chickens have pullybones nowadays?

Mom always baked five loaves of bread on Saturday morning, and one or two coffee cakes with any dough left over. She’d knead the dough in a small washtub, then divide it into the five bread pans. There’s just nothing finer tasting than homemade bread fresh out of the oven. It filled the house with a delicious aroma too.

Mom lived to be 83 years old, outlasting my father by fourteen years. Her last few years were not pleasant ones. She developed Parkinson’s disease which was slowly debilitating. Her mind remained sharp through all of that, but by the end she had lost control of all bodily functions. She was a proud woman, and it embarrassed and humiliated her to become so helpless. Through it all though, she never lost her Christian faith. She loved her grandchildren. I think she thought of Laura as the daughter she always wanted, and when Laura was killed, Mom just gave up.